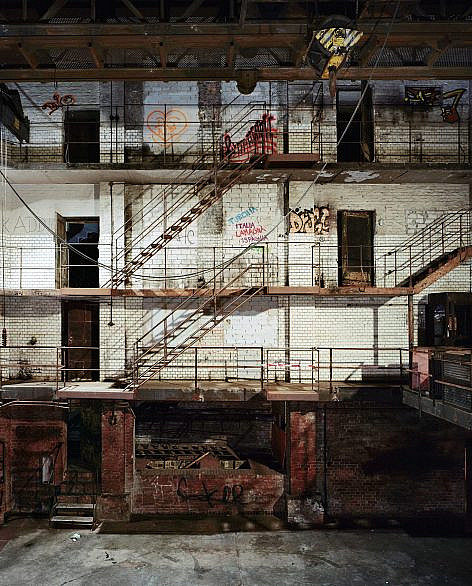

After the Berlin Wall came down, ewerk was used for an entirely different purpose that provided a springboard for the facility’s international renown. But before this new page in ewerk’s history could be turned, the buildings of the former central power plant were used as a repository for street lights (until 1991). During this period, the first theatrical pieces were performed at the facility, such as the one by Jannis Kounellis during the “Endlichkeit der Freiheit” (“Finitude of Freedom”) show.

But after the repository was cleared out, things really got going when, in 1992, Andreas Rossmann “discovered” ewerk, which three years after the fall of the Berlin wall was still for the most part shut down except for a few residual energy supply functions. In his capacity as location scout, Rossmann was looking for a kind of construction of which a fair number were to be found in the center of Berlin at that period. These were buildings whose architectural particularities, physical condition, or geographic location – or sometimes pure chance – made them suitable for celebratory subculture events and that greatly contributed to making Berlin a habitat in which robust and positive dimensions could be integrated into the emerging post Cold War world. One such institution, known as Planet Club, had set up shop at various locations in Berlin’s somewhat chaotic eastern half, and Rossmann was now seeking yet another new location for it.

Rossmann then rediscovered the spectacular Mauerstraße location for which an initial project was planned in early 1993, the so called Evidence Party, which was held in the current building F with Low Spirit and Westbam performing. It was a bitter cold evening and the now legendary fire installation was more reminiscent of the Bronx than Berlin.

The Mauerstraße location was found to be so intriguing that continuous efforts were made to develop it into something more permanent, and this culminated in the (re)opening of the club in April 1993, with DJ Clé’s spinning the first record. As a club, ewerk soon became a very special venue in Berlin’s high-powered pop music scene, a status that indisputably was fostered by the congenial chemistry of the self-styled “glamor crew” consisting of Hille Saul, Andreas Rossmann, Ralf Regitz and Lee Waters. Hille Saul, who was the soul of the venue and the guiding hand behind the club’s music, initiated a series of events such as Saturday TWIRL featuring ewerk regulars and international guest DJs, as well as Dubmission on Fridays with regular Paul van Dyk. Other formats were developed as well such as Lee’s Ranch, and there were ad hoc modes such as Love Parade events.

ewerk soon distinguished itself from the panoply of diversions Berlin had to offer and soon achieved cult status in large measure thanks to the attention it received from a number of renowned German and international institutions, including (to name but a few) the Prodigy concert during the 1994 MTV European Music Awards 1994 and the Chromapark Techno Art Exhibition (1994-1996) which combined media events with the art of partying. The performers at these events included 3D Luxe, Elsa For Toys, Attila Richard Lukacs, Ali Kepenek and Wolfgang Tillmans.

The club’s success at bringing together an extremely diverse group of cultural happenings in one place – ranging from a Massive Attack concert to a Versace gala dinner to Katharina Thalbach’s production of Don Giovanni in cooperation with Christoph Hagel and Mediapool – shows that ewerk was one of the top clubs in the 1990s in terms of both its underlying concept and its track record.

The club counted among its regulars Clé, Woody, Westbam, Jonzon, Terry Belle and Disko, and there were guest appearances by the who’s who of the techno scene, including (to name but a few) Derrick May, Juan Atkins, Kevin Sounderson, Carl Cox, Laurent Garnier, Sven Väth, Hell, and Paul van Dyk.

The ewerk of this period and the attendant club generated a host of legends, many of which can be justly described as exaggerated or blatantly false. But these narratives remain living proof of the major extent to which the music scene was associated with the ewerk club back then. At the same time, heart rending scenarios were constantly played out just outside the club entrance when people that were dying to get in were turned away. And inside too a number of events gave rise to memorable stories such as the time Laurent Garnier, upon entering ewerk, got down on bended knee and expressed a fervent desire to be buried at ewerk. An even more dramatic event occurred when a restroom attendant caught supermodel Naomi Campbell doing something illegal in the restroom and dragged her out of the stall by her hair.

The club closed its doors in 1997, but definitely ended its days with a bang rather than a whimper, i.e. a three day long event that attracted 4000 people from around the world who were fortunate enough to experience the club at its whitest of white heats. The trembling of the double bass from this final event still reverberates in the minds of Berlin officials, who were weren’t exactly thrilled to learn that one of the club’s former honchos was still trying to find a new function for ewerk.

The most important legacy of the ewerk club is that in retrospect, all concerned – guests, artists and management – felt as though they were part of something that was not only unique, but that was also part of a relaxed political and institutional ambience that allowed for non-replicable creativity and even some insanity. The club remains one of Berlin’s most powerful and beautiful memories of the post-communist period, and this little segment of memory lane will undoubtedly bolster the legendary status of the club as time goes by.

After the club closed, beginning in 1998 various attempts were made to find a long term and sufficiently challenging role for ewerk, but all of these efforts failed for various reasons. These projects included an energy forum, as well as a plan to create office space for “new economy” businesses. This resulted in an increasing number of requests to use the space for individual events.